| Jump to: What we do · Intended impacts · Key insights · Collaborators and funders · Our team · Updates · Outputs |

Urban green infrastructure can help in recovering from hazards or provide safety nets. Urban agriculture, hill forestation, terracing, green public open spaces, and clearing invasive alien plants can all help to reduce erosion, filter grey water, provide medicine, timber, fodder, windbreaks, and shade, promote the provision of downstream water, regulate flood shocks, reduce sedimentation and run-off, and complement drainage.

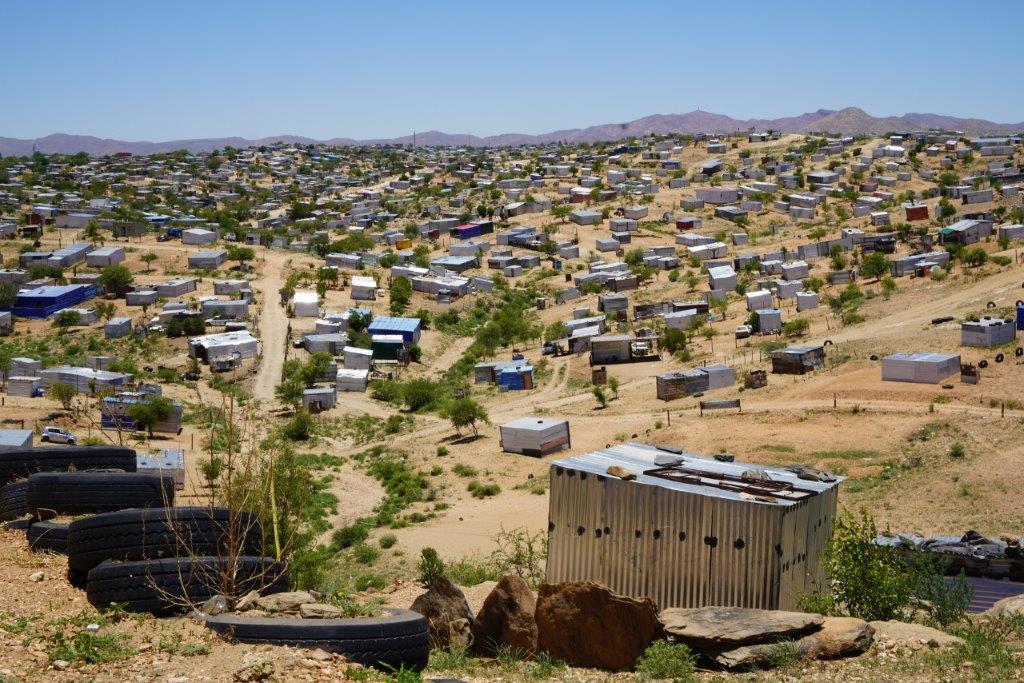

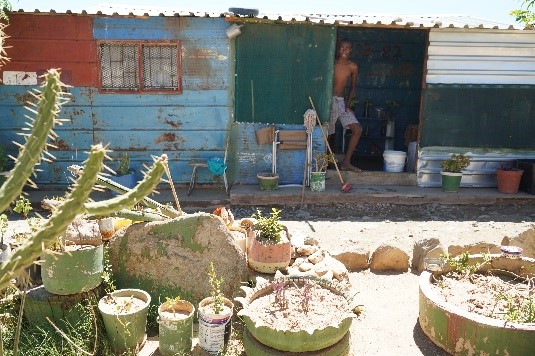

Fifty-nine percent of Sub-Saharan African urban populations live in informal settlements (UN-HABITAT 2019), expected to triple by 2050. Despite an increase in improved housing from 11% to 23% between 2000-2015, 53 million urban Africans were still living in unimproved housing in 2015, often in highly overcrowded conditions, with large deficits in city infrastructure and public service provision, and in hazardous sites such as riparian corridors and on steep slopes (Shatterthwaite et al. 2018, Tusting et al. 2019). These complex natural and socio-cultural dynamics, combined with climate variability, severe and persistent drought, extreme rainfall and heatwaves, expose much of the population to high levels of risk, and threaten an irreversible collapse in ecosystem diversity and functioning (Thorn et al. 2015, Dodman et al. 2017, Shatterthwaite 2017).

Ecosystem-based solutions in the form of ecological (or green) infrastructure (EI or GI) have emerged as spatial planning tools for ensuring functional networks of natural and semi-natural areas. They demonstrate the importance of ecological systems as part of the infrastructural fabric that supports and sustains society and builds resilience (Harrison et al. 2014, Lindley et al. 2018, Cilliers 2019).

In various cases across Sub-Saharan Africa, well-functioning ecosystems provide diverse provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural services to society that can buffer against risks arising from droughts and floods, and can reduce the loss of lives, assets and critical infrastructure (Kaoma and Shackleton 2014, Seburanga et al. 2014, Adegun 2018), with benefits for physical/psychological health, social equity and wellbeing (Shackleton et al. 2015, Kopecka et al. 2018). Urban green infrastructure (UGI) can lengthen the life of existing built infrastructure, make areas more attractive for investment and require minimal input and maintenance. Yet, informal urbanisation continues to intrude upon and undermine ecological space (e.g., illegal dumping, open defecation, criminality), while encroachment on formal green spaces that can be of ecological importance (Adegun 2019), especially urban parks, is common (Bhattacharya 2014, Israt and Adam 2017). Moreover, most research on UGI outcomes to enhance climate resilience has been conducted in formal settlements in the Global North, while the unique sociocultural context, and spatial challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa means that Africa must not necessarily emulate Western models of green infrastructure planning.

Producing better strategies that reverses this trend requires more fine-grained data that is impact-relevant, new metrics for risk and adaptation, and instruments that account for uncertainty in decision making. To improve predictions of future climate change without knowing the exact scale of risk, a more comprehensive assessment is needed to identify where benefits outweigh costs, and when to transfer, avoid, reduce, or accept risk.

What we do

Unplanned settlements in Northern Windhoek, Namibia are often located in hazardous zones, including on slopes and in river beds, and are regularly exposed to climatic hazards.

Our project combines multi-scalar institutional analysis, empirical data collection, and participatory scenario planning for a comprehensive understanding of the synergies and trade-offs of UGI for climate adaptation in the peri-urban areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. We focus on the overabundance or scarcity of water, given the growing need to secure a reliable water source to cities with quality and supply-demand constraints, and because cities typically rely heavily on engineering infrastructure for water storage/purification.

The project has four interlinked objectives:

-

Determine the impacts of seasonal variability on water supply in rural and peri-urban areas, and adaptation pathways;

-

Assess the comparative impacts of water-related UGI on ecosystem service provisioning and wellbeing in peri-urban areas;

-

Identify the barriers to the mainstreaming of UGI in peri-urban settlements for climate adaptation; and

-

Examine diverse, plausible scenarios to achieve desired futures for 2030 and 2063, using participatory scenario planning.

The main empirical work will use a comparative, transdisciplinary, in-depth case study research design. Work will focus on two peri-urban areas in southern and East Africa (Windhoek, Namibia and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania) that effectively represent water-related EI and associated hydro-climatic risks, and offer broad regional coverage, a range of population sizes, inland verses coastal locations, and growth rates.

Intended impact

Solid waste disposal is limited, as are other interim services such as drainage, leading to dumping and contamination. Only 40% of urban populations in Sub-Saharan Africa have access to improved sanitation, and most informal settlement populations rely on communal or public latrines. Consequently, health burdens are high, particularly infectious, parasitic, communicable, and non-communicable diseases.

Through our work we aim to:

-

Improve our understanding and ability to assess likely future impacts of climate change on patterns of peri-urban settlement development.

-

Identify adaptive landscape development trajectories, and what key factors emerge as critical for maintaining social-ecological urban resilience.

-

Build a cadre of young African scientists working on adaptation, enhance technical capabilities to address shared problems, establish a platform for deep collaboration, and leave an institutional legacy through a university programme.

-

Engage closely with municipal and city authorities at the subnational level to help generate policy-relevant evidence and provide clear place-based insights into developing pragmatic, long-term risk reduction strategies, climate action plans, informal settlement upgrading guidelines and urban planning and design.

-

Inform the upcoming assessments on peri-urban resilience of the International Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

-

Use case studies to act as exemplars for other similar initiatives around the world, and extrapolate scientific principles on broader spatial-temporal processes.

-

Make more seamless connections between the urban and rural in order to address future challenges.

Key insights

Urban green infrastructure enhances aesthetic value, and creates opportunities for social interaction and community cohesion. It also fosters inclusion and attachment to space.

-

UGI can help recovery from hazards (e.g., poles for construction), provide a safety net (e.g., wild foods in times of drought), filter grey water, provide timber, fodder, windbreaks, and shade, promote the provision of downstream water, reduce sedimentation and run-off, complement drainage, and create opportunities for social interaction, community cohesion, foster inclusion and attachment to space.

-

UGI must be understood as part of the infrastructural fabric and economic good, rather than a “luxury and visual good, in comparison to more pressing needs”, particularly in small to medium sized cities where low-income and other marginalised urban residents are typically more dependent on ecosystem services than higher-income groups.

-

There is an urgent need for national governments, international agencies, civil society organisations, and public-private partnerships to support more capable, creative, accountable, better-resourced municipal governments. Improving community rights, state relations, community integration and reforming policing is essential for achieving successful adaptation interventions.

-

Integrated planning needs to prioritise capturing multiple ecosystem services and functions, zone according to ecological and historical parameters, ensure quality and accessibility in relation to function and form, and promote more even distribution in high- and low-income neighbourhoods (including backyard dwellings). Land use land cover change needs to be monitored, and urban ecosystem services not managed intensively for one type of ecosystem service at the expense of others.

-

With changing precipitation regimes, residents, conservation agencies, private businesses and local authorities need to work together to maintain and restore degraded wetlands, riparian corridors, and rivers to enhance flood regulation and water purification functions, and reduce contamination and the spread of communicable/waterborne pathogens.

In December 2020 Dr Jessica Thorn presented key insights as a fellow at the NEF Global Gathering.

Project Team

The project is jointly coordinated by the ACDI and the York Institute for Tropical Ecology, Department of Environment and Geography at the University of York. Key collaborating research partners include FRACTAL, University of Dar es Salaam, University of Namibia, University of Oxford, Slum Dwellers International, and Stockholm Environment Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*For more information about the project, please contact Jessica Thorn at jessica.thorn@uct.ac.za

Project updates

Announcements and events

-

Jessica Thorn is a guest editor for a special issue in the Sustainability journal, titled: "Environmental Policy Design and Implementation: Towards Sustainable Society". This special issue is now open for submission (by 30 September 2020). Read more.

-

International Conference on Innovation and Interdisciplinary Solutions for Underserved Areas (InterSol 2020): Event details: 8-9 March 2020 in Nairobi, Kenya. Read more.

- Scenario Planning workshop: Event details: February 2020 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Project outputs

- Report of Urban Ecolution: Participatory Scenario Planning Workshop

- Blog Post: Insights from assessing household perception of Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI) in the informal settlements of Dar es Salaam - March 2020

- Blog Post: Exploring the potential for ecosystem-based climate adaptation in informal settlements in Windhoek, Namibia - October 2019

- Blog Post: Using scenario planning to determine development pathways for Windhoek’s informal settlements - October 2019

Collaborators and funders

This research is funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre African Women in Climate Change Science fellowship, Climate Research 4 Development fellowship, the University of York with the support of the African Academiy of Sciences, and the African Institute of Mathematical Sciences. We are working in partnership with University of Namibia, Namibian University of Science and Technology, University of Dar es Salaam, University of Oxford, Stockholm Environment Institute, Namibian Chamber of Environment, local municipalities and shack dwellers federations.