Exploring the potential for ecosystem-based climate adaptation in informal settlements in Windhoek, Namibia

By Amayaa Wijesinghe (MSc Biodiversity and Conservation Management, University of Oxford)

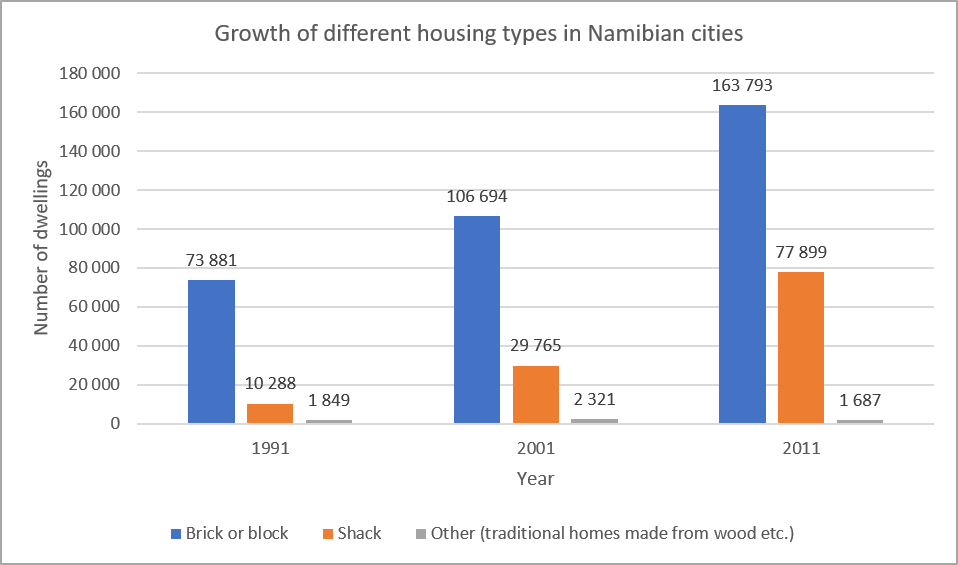

Growth of informal settlements in Windhoek

After independence from South African apartheid in 1990, rural-urban migration increased exponentially, largely from the Northern agro-pastoral region of Namibia, where drivers of migration included unemployment, disaster-struck agricultural systems, and removal of restrictive apartheid laws on peoples’ movements. Most individuals who came to cities could not afford formal housing, and instead resorted to building temporary shacks on government land while “waiting for plots to come online”, usually on the periphery of former black townships.

In Windhoek, as in other Namibian cities (Figure 1), these peri-urban informal settlements are now expanding at an accelerated rate compared to formal areas, and the vast majority of shacks still ‘illegally’ occupy land owned by the local government authority, the City of Windhoek (CoW). These areas are characterised by limited access to basic services.

The informal settlement located in the Tobias Hainyeko Constituency of Windhoek, with homes built just 3-4m away from the riverbeds in some instances. These streams can become raging rivers when the rains fall. In 2018, a woman and child drowned when their shack was washed away, and flooding in shack homes is common during the height of the rainy season November-January. However, there may be scope to manage and plan settlements to allow restoration of riparian vegetation for DRR and climate adaptation. This must be explored further.

Impacts of climate change

This proliferation of informal settlements poses a complex developmental challenge to the CoW, NGOs, and citizens at large. Compounding this challenge further, it is predicted that Namibia (among SSA countries) may bear the brunt of global environmental change under various climate change scenarios (IPCC, 2014 – Box 3.1). Namibia is already facing a prolonged drought period, stretching from 2013 to the present. Future impacts could include longer and more frequent drought periods, increased volumes of water when rain does fall (causing flash floods), as well as higher temperatures, exacerbated by the urban heat island effect (Shikangalah and Mapani, 2019; SEI, 2019).

Role of natural ecosystems in climate adaptation

In many other parts of SSA, including neighbouring South Africa, governments and local authorities have started exploring and mainstreaming green infrastructure (or ecological infrastructure) and ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) measures to help cities adapt to climate change. As part of my research for my MSc thesis in Biodiversity and Conservation Management at the University of Oxford, co-supervised by Dr Jessica Thorn, I used key informant interviews (n=22) and focus groups (n=20) to understand the present and potential utility of EbA in Windhoek. In particular, I explored specific opportunities and barriers for adoption of EbA for disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate adaptation in Windhoek, with a special focus on informal settlements in the Northern and Western part of the city.

Through a qualitative analysis of the data, I determined that there are several key components of ecological infrastructure present in Windhoek (Table 1). These components provide several ecosystem services to residents of Windhoek’s informal settlements as well.

| Ecological infrastructure identified | Type of ecosystem |

| Ephemeral rivers | Freshwater |

| Riverbeds and buffer zone | Riparian, savannah |

| Trees in surroundings | Dry savannah |

| Vegetation on hilly slopes | Dry scrub and bush |

| Urban agriculture | Settlement |

| Dams | Freshwater |

| Vegetation surrounding dams | Riparian, savannah |

Our research found that provisioning services include (i) fuelwood for energy (cooking) and resale (income generation), (ii) grasses sourced from the city’s riverbeds and tree pods from Acacia trees (resale as fodder for livestock), and (iii) fruits and vegetables from urban gardening plots. Regulating services include the regulation of storm water flow, and prevention of soil erosion and dust formation. Scenic sites, such as the Goreangab Dam area, provide cultural services such as recreation.

Grass for sale by the roadside of the Khomasdal constituency in Windhoek. It has been freshly cut from the riverbed just behind, and stacked in order to attract buyers, who would use it as fodder for livestock.

However, the ecological infrastructure that could provide these (and many other) services are degraded due to unsustainable natural resource use patterns, such as indiscriminate cutting of trees and shrubs as fuelwood. Additionally, there is low awareness about the important co-benefits for DRR, livelihoods, and human wellbeing that management of biodiversity could provide.

Constraints and trade-offs

A key finding of the research was the contribution that ecosystem goods (such as sale of firewood, grasses and pods) make to the informal economy in Windhoek. There are trade-offs associated with continued exploitation of these natural resources, environmental degradation, and the livelihoods of the economically vulnerable. The costs, benefits, and appropriate management strategies must be explored further.

Additionally, the acute survival needs created by poverty and lack of basic services in informal settlements (e.g., a lack of functioning toilets forcing residents to use riverbeds to openly defecate), leads to a lack environmental stewardship, lack of conscientiousness in use of common goods, and mismanagement of natural ecosystems. CoW divisions like Parks or Environment, who manage natural areas in the formal part of the city, lack the mandate to effectively manage the same areas in informal settlements, which is also a critical barrier.

Other constraints for mainstreaming EbA into policy and planning include: (i) accelerated and unplanned expansion, (ii) absence of land tenure and feeling of belongingness, (iii) lack of resources and expertise, (iv) lack of effective channels for widespread information dissemination, (v) inadequacy of EIA process, (vi) financial constraints, and (vii) disconnection from nature due to urban lifestyle and aspirations.

Implications

Windhoek is currently in the process of drafting its Integrated Climate Change Strategic Action Plan (ICCSAP), spearheaded by the CoW. My study shows there are robust opportunities to mainstream EbA interventions into this ICCSAP, as part of a larger adaptation plan for Windhoek’s most vulnerable. However, if EbA interventions are to be successful, residents of informal settlements must be directly involved in identification of focal projects, planning, implementation and monitoring. Context- and location-specific, transdisciplinary measures to overcome constraints must also be determined by all relevant stakeholders.

References

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., D. Jacob, M. Taylor, M. Bindi, S. Brown, I. Camilloni, A. Diedhiou, R. Djalante, K.L. Ebi, F. Engelbrecht, J.Guiot, Y. Hijioka, S. Mehrotra, A. Payne, S.I. Seneviratne, A. Thomas, R. Warren, and G. Zhou, 2018: Impacts of 1.5ºC Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I.Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T.Maycock, M.Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. In Press.

SEI (2019) Helping Windhoek plan for climate change. Link: https://www.sei.org/featured/windhoek-climate-change-plan/ (Accessed 30 Sep 2019)

Shikangalah, R. N. and Mapani, B. (2019) ‘Precipitation variations and shifts over timeâ¯: Implication on Windhoek city water supply’, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth. Elsevier, (August 2018), pp. 0–1. doi: 10.1016/j.pce.2019.03.005.

Weber, B. and Mendelsohn, J. (2017) Informal settlements in Namibia: their nature and growth.