Launching a research programme to bring diverse stakeholder value systems together for climate-resilient urban development in Central and Northern Namibia

By Dr Jessica Thorn and Amayaa Wijesinghe, ACDI UCT and University of York

The dynamic confluence of drought and urbanization in Namibia

In 2018, the state of informal settlements in Namibia was considered a humanitarian crisis, and in 2019, following six years of drought, a state of emergency was declared. The situation is serious. Growth of informal settlements (between 7-11% per annum) coupled with exposure to climate-induced hazards (e.g. Drought, rising temperatures, falling dam levels, localized flash flooding), continues to erode basic infrastructure, public services, and ecosystems, while entrenching inequalities. These factors threaten future progress towards achieving healthy communities, regional economic development, and multiple sustainable development goals. In these circumstances, proactive engagement and inclusion of local stakeholders - especially marginalized voices - into urban planning, has the potential to improve decision-making, reduce historical inequalities, and promote benefit-sharing and social-ecological resilience.

Yet, very often key social and economic policies that affect the lives and well-being of families, communities and society are made by a small group of policymakers, politicians and the usual ‘key’ stakeholders. This excludes the very people who may be affected by the implementation of those policies, especially poorer, marginal and itinerant groups that lack strong political representation, including informal settlement residents. Limited tools have shown to effectively incorporate diverse perspectives into policies. Meanwhile, few attempts have been made to assess the drivers of unplanned informal settlement expansion, especially their reciprocal interaction with social-economic and environmental impacts (e.g., food, water, energy, land and livelihood security), and also how these feed into current planning processes, both now and in the future.

Introducing Peri-Urban Resilient Ecosystems (PURE)

The purpose of the Peri-Urban Resilient Ecosystems (PURE) research programme is to help reverse that trend and bridge this particular gap in Namibia. We do this by exploring how collaborative participatory methods that focus on value systems and future development trajectories, can bring together diverse stakeholders to inform the development of just and inclusive climate-resilient urban policy and planning. In particular, PURE will focus on Namibia’s first municipal-level strategy to operationalize the Nationally Determined Contributions, which is the Integrated Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (ICCSAP).

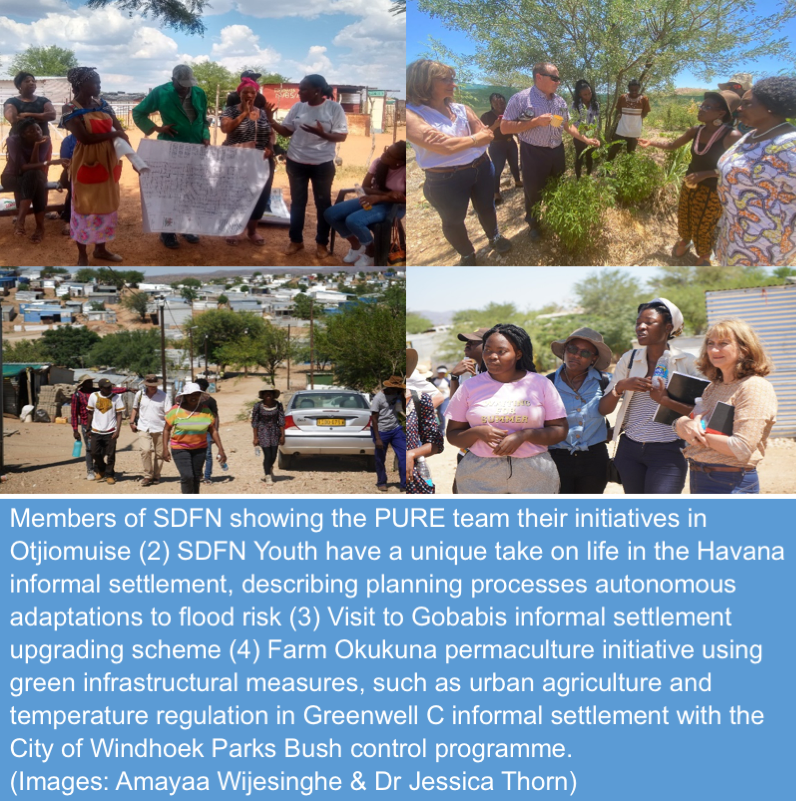

Presently, the programme is engaged in a widespread data collection exercise in Central and Northern Namibia, working in the informal settlements of Windhoek, Gobabis, Otjiwarongo, Tsumeb, Oshikati, Ondangwa and Outapi. The project is supported by the UK Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), and brings together eight organizations from Namibia, South Africa and the UK, namely the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), University of Namibia (UNAM), the Shack dwellers’ Federation Namibia - Namibian Housing Action Group (SDFN-NHAG), University of Cape Town, together with the University of York, University of Winchester, ICLEI Africa and the Stockholm Environment Institute – York (SEI-York).

Project launch

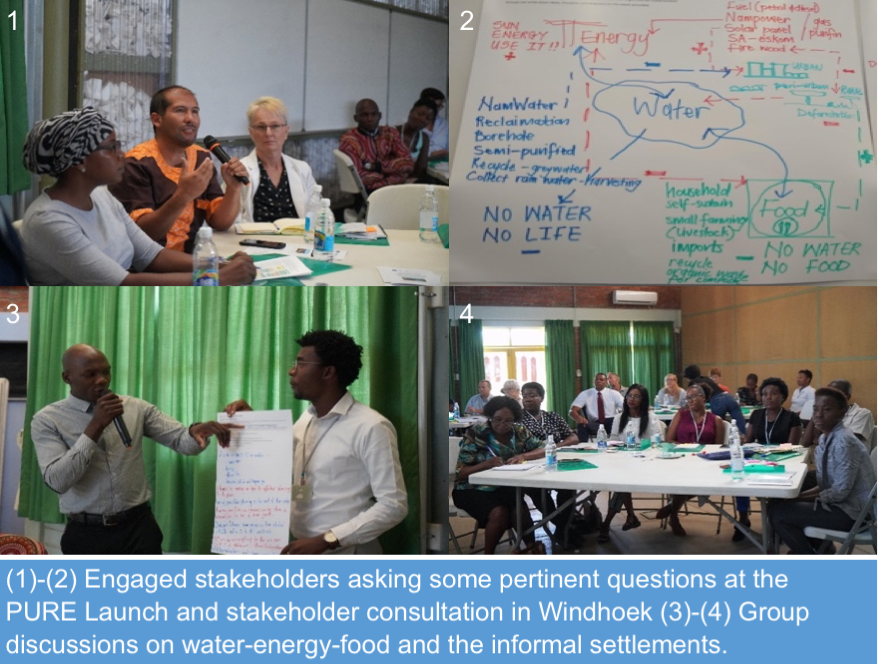

This stage of the programme was launched with stakeholder consultation workshop, followed by a two-day intensive working session and fieldtrips on the 28-30 of January 2020 at the Habitat Research and Development Centre, in the capital Windhoek. Fifty-eight stakeholders participated in the workshop to create an understanding of where the programme’s future priorities should lie. A range of perspectives were included in the dialogue, representing municipal, community based, private sector, donor and non-governmental organisational approaches from the sectors of disaster risk reduction, urban agriculture, water management, community development, land and housing, and environmental management within the city.

Political support

The launch was officially opened by Counsellor Fransina Ndateelela Kahungu, the Honourable Mayor of Windhoek, who spoke of the immediate need to join together to address informal settlement development and increase awareness and dialogue surrounding climate change in urban planning in Windhoek. She appreciated the presence of international researchers willing to work together with local partners in bringing these objectives to fruition and called on City of Windhoek officials to support the project on the municipality authority’s behalf. Deputy British High Commissioner, Hon. Charlotte Fenton, then emphasised the developmental challenges that lie ahead in the face of climate change and reiterated the UK government’s support for multilateral initiatives and research that would focus on increasing the resilience of Namibia’s people. The designer and architect for the centre, Architect Nina Maritz, gave an introduction to the sustainable materials and methods used to design the centre which was chosen as an example of sustainable construction and environment-integrated passive design principles, using existing water contours and local materials, while also being a training centre for low income citizens.

State of evidence

Dr Adam Hejnowicz, of the Universities of York and Sheffield and Co-Investigator for PURE, introduced futures thinking and scenario-based policymaking to the participants, describing how it had come to the forefront of science-policy research, as it offered the chance to envisage environmental or policy-based change.

“We will apply a participatory values-based scenario modelling approach allowing diverse stakeholders, including marginalized rural-urban communities, to articulate their perspectives concerning future urban policy planning processes. Our hope is that this will encourage the co- design of equitable future climate resilient urban development pathways and serve as a future policy model for the country, with wider application across the African continent in health and wellbeing”, he said.

Kornelia Lipinge, on behalf of the University of Namibia, then presented the latest evidence concerning climate change impacts, suggesting that global average temperature change of 1.5 degrees will result in a higher average change in Namibia, with concomitant drought frequency, slow-onset temperature change, and intensified rainfall when rains do occur. Dr Anna Muller of SDFN-NHAG spoke about the participatory method of data collection in informal settlements used by the NGO, known as the Community Land Information Programme (CLIP), used as a prerequisite to the upgrading process in Namibia. Olavi Makuti of the City of Windhoek - Health and Environment Division concluded the session, describing the scope of the municipal ICCSAP response plan (currently in review).

Steering urban nature-based solutions at the municipal level

In session two, Dr Jessica Thorn and Amayaa Wijesinghe put forward findings and insights gained from ACDI’s sister project Urban Ecolution, through fieldwork and scenario planning ongoing since November 2018. This explores the role of Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI) in supporting climate adaptation in Windhoek’s informal settlements (Table 1). Many other ongoing initiatives provide useful examples of successful research in action. For example, Jess Kavonic of ICLEI Africa, drew from experience in other parts of Africa, working with local governments to protect and revitalize their urban biodiversity and natural assets in a programme ‘Urban Natural Assets Africa’. Dr. Ibo Zimmermann of the Namibia University of Science and Technology described work on efficacy of various practical methods to grow trees and food plants successfully in dryland Windhoek. Uakazuvaka Kazombiaze of the City of Windhoek Parks Division described work to maintain public open spaces and bush control.

Table 1. Key insights from a recent household survey of residents’ perceptions of Urban Green Infrastructure in Windhoek’s informal settlements (Thorn et al., in prep).

|

What is UGI? |

Ecosystem services |

Constraints for optimisation |

Recommendation |

|

Green areas along rivers, children’s playgrounds, football fields, green areas along roads, health clinic garden, and planted trees are considered green spaces. |

Shade, air purification, carbon absorption, temperature regulation, fuelwood for household, psychological comfort, fruits, medicinal resources, beautification, and improvement of soil quality. |

Open illegal dumping, petty crime, drug trading, disease spread, the erection of unauthorized structures, land scarcity with population growth, invasive species, large infrastructural developments, equitable development, basic service delivery, resource consumption, rapid urbanisation |

In-situ upgrading policy of the municipality authority must consider these green spaces, public-private partnerships and environmental education around these spaces |

Urban water energy food nexus

A carousel session in the afternoon focused on the Urban water, energy and food systems. Critical questions guided the conversation, such as those outlined below, with an example of a group output shown in Table 1 and Photo 2 below. Energetic discussions were moderated by Royal Mabakeng of the Integrated Land Management Institute (NUST), and Dr Farayi Zimudzi of UNFAO.

Table 2. Summary of key insights from WEF nexus carousel

|

Theme |

Water |

Energy |

Food |

Landscapes |

Land ownership |

|

Question |

How are informal settlements responding to current resource scarcity and climate change, and what is undermining residents’ adaptive capacity? |

How do you democratize the energy systems by connecting informal settlements to the main energy sources, and reduce reliance on fossil fuels and wood? |

What are the prospects and barriers for urban agriculture in Windhoek? How do people access food in times drought and what are the food resource flows? |

What are the links between urban and rural WEF resource flows and wider production supply chains, and how does this differ across time (e.g., seasons) space (e.g., landscapes) or risk exposure? |

How does land use and tenure in Namibia influence access to public services, housing and resource use? What is the land-use priorities of different communities of users? |

|

Core problem |

Limited access to water |

Limited access to electricity |

Food deserts and limited local production |

Deforestation and water scarcity |

Exponential growth in urbanization without planning |

|

Constraints |

Contamination, vandalism of standpipes, affordability |

Cost of transport, cultural habits, poverty, spatial planning, monopolization |

De-ruralization, rural urban migration, aging labour force, unemployment, drought |

Reliance on food imports, fuelwood |

No financing options for the poorest, lack of proactive planning, apartheid legacy, affordability |

|

Solutions |

Budgeting, harvesting, land tenure, formalization of settlements |

Biogas, solar cooking, decentralization mini grids, public service provision |

Education, sustainable water management, urban agriculture, indigenous techniques |

Recycling organic waste, solar energy, household self-sustenance, small livestock farming |

Alternative housing financing models for the poor, community participation in servicing |

|

Enablers |

Good governance, decentralization |

Subsidies, local networks, saving groups |

Existing urban initiatives to be scale up, municipal support |

Water reclamation, recycling grey water |

Decentralization, affordable servicing options |

Democratizing policy development - Leaving no one behind

The final session of the day explored how underrepresented voices could be brought into the conversation around risk and climate change. Jane Gold, lecturer at the Faculty of Natural Resources and Spatial Planning at NUST, moderated the panel.

The panel discussion focused on the importance of

- Long term planning and having a road map of how to achieve desired futures

- Participatory policy development ensuring grassroots needs are accounted for

- Raising the awareness of residents of the value of the natural environment

- Building local leadership

- Learning from local examples UGI through intra-country exchanges (e.g. Kavango and Windhoek)

- Translation of policy to implementation

- Collaboration

- Benefit sharing

- Equitable development

“If shack dwellers are not involved in decisions about their own surroundings, they will not care, and any initiative will fail. Most often, informal communities are scared to voice out their opinions, but they need to be reassured that their input is valid, and their voices are heard. The youth must also get involved, because there are new livelihood opportunities that they will be able to use. It is important to include all these stakeholders from the get-go, and not assume what their needs would be.”

Ms. Ina-Maria Shikongo – Trainer, Eloolo Permaculture Initiative and Organizer, Fridays for the Future Windhoek

Key take home priorities identified for PURE from the project launch

- Engage officials of the local authorities in all stages of PURE, and endeavour to identify pathways to influence varying development and environmental policies, particularly those on climate action

- Facilitate co-production of pilot initiatives through local ownership.

- Explore effective methods to transfer knowledge about climate change and green infrastructure to the communities in informal settlements.

- Establish “design studios”, where solutions for green infrastructure and ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) in cities can be co-designed by beneficiaries and researchers - previously has been used by NUST and SDFN-NHAG for upgrading work.

- Bring unique international, regional, and localized insights to the project, and enhance local capacity through field work and a collaborative proposal and grant writing workshops later in 2020.

- Document the innovative, dryland-adapted climate adaptation interventions that Namibians already adopt in an urban context and disseminate findings.