The Food, Energy, Water, Land and Biodiversity (FEWLB) Nexus project looked to inform decision making and project development to foster sustainable resource use and development within the Berg River catchment area. The project started in October 2013 and was funded by the British High Commission and the Cape Higher Education Consortium (CHEC). ACDI implemented this project in collaboration with the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning.

Nexus thinking is developing internationally in an attempt to understand and deal with the interdependencies which exist within complex natural and human systems. This is becoming increasingly important as we begin to push against the planetary boundaries of resource use, and emerging resource constraints become a limitation to economic development. Thus, an integrated consideration of food, water, energy, land and biodiversity is essential in local economic development planning. Decisions which benefit some components of the nexus can have negative impacts on other components. When these trade-offs are identified and quantified, decisions can be adapted or mitigation measures put in place to optimize overall benefits. Future pressures, such as climate change, also need to be considered.

The Berg River catchment represents an excellent example of an economically important regional system under high resource extractive pressure at the nexus of water quantity and quality, food production and energy supply, within the wider context of a rich biodiversity and intensive land use. Pollution in the Berg River catchment is a cause of great concern especially to communities, farmers and industries in the various municipalities of the West Coast and Cape Winelands regions. In addition, there is increasing concern that the water will not be adequate in future to service the entire region – in particular, that the planned industrial development at Saldanha Bay will be constrained by the predicted future resource unless the management of the resource is changed significantly. This is complicated by the high demand on Berg River water resources by the City of Cape Town. Water must also be allocated to the ‘ecological reserve’* which provides critically important environmental and social services.

In relation to government powers and functions, management of the Berg River system straddles all three spheres of government, involving local, provincial and national government responsibilities. Given the fact that the FEWLB nexus represents a complex system, cooperation between National Government, the Western Cape Provincial Government, District and Local Municipalities, other Berg River stakeholders and the academic institutions in the province becomes increasingly important. A number of studies are already focused on the Berg River/Saldanha Bay area. The work undertaken in this research project does not duplicate what is already underway, but adds to and complements current research work, and shows the way for future more in-depth research.

About the Berg River

Due to its position in a Mediterranean-type climate region, rainfall is concentrated during the cool winter months, with a steep gradient from the south-eastern upper catchment (>1200mm per year) to less than 300mm per year at the north-western estuary. Summers are dry and can get very hot, particularly on the more northerly interior plains at the foot of the mountains. Cooler conditions prevail in the mountains and along the windy coastline. The area is geologically diverse and includes Table Mountain sandstone, granite and Malmesbury shale, with extensive coastal sandy areas of recent geological origin. The combination of climate and soils results in patches of high fertility, but large areas of lower potential productivity suited only to dryland farming.

This catchment is a significant water source on a regional level. The area is an integral part of the Western Cape Water Supply System (WCWSS), which focuses both on ensuring adequate water supply for the metropolitan area of Cape Town and surrounds, as well as supplying the needs of irrigators and some rural towns. Major users of the water within the catchment include irrigated agriculture (grapes and fruits, ca. 54% of water resources), processing of agricultural produce, municipalities (urban water supply, wastewater treatment), and industry (mainly around Saldanha Bay and Paarl/Wellington). Water is abstracted primarily from surface water (57% of total water resource), although groundwater (8%) is used in some towns such as Porterville and Hopefield.

A few larger dams form part of the WCWSS. They are the Berg River Dam (completed in 2007) and Wemmershoek Dam, both in the upper catchment, the Voëlvlei Dam and the Misverstand Dam. Substantial amounts of water (27% of the water resource) are transferred into the basin during the summer months from the adjacent Breede River catchment to supplement the water resource. Many hundreds of small private farm dams also provide an essential water resource for irrigated agriculture. Nevertheless, the Berg River system is under water stress and new water augmentation schemes will be required by 2022 in order to avoid deficits. New sources of water are likely to become increasingly costly.

Poor water quality has been identified as a major concern in the Berg River system, particularly further downstream. The reasons range from agro-chemical runoff from intensive farming operations, and ageing and under-capacity waste water treatment facilities for burgeoning settlements, to a natural tendency towards high levels of salinity from tributaries underlain by shales of marine origin. This pollution situation threatens the viability of export-driven agriculture and industrial processes in Saldanha Bay (e.g. steel production) which require water of a minimum quality standard. Various initiatives and projects are underway to address this, notably the Berg River Improvement Plan (BRIP).

Roughly sixty percent of the Berg River catchment is agricultural, with primarily grapes and deciduous fruits being cultivated intensively in the eastern regions, and small grains (e.g. wheat, canola) and livestock (cattle and sheep) dominating the drylands to the west. Significant foreign revenue earnings flow from the export of fruits and wine/spirits, with most of the production being exported. Other products include vegetables, indigenous ‘fynbos’ flowers (Protea and others), olives, dairy products and poultry. Agriculture also drives much of the secondary economy in the form of fruit and vegetable processing, including canning, drying, juicing, and jam production.

Extensive land use change from natural fynbos and Renosterveld vegetation to agriculture and settlements has placed the rich biodiversity under threat. The area forms part of the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest of the six Floral Kingdoms in the world, but containing extraordinary high levels of terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity and endemism. This biodiversity ‘hotspot’ has immense intrinsic value for the healthy functioning of the ecosystems of the catchment, as well as having great economic value associated with wildflower harvesting and ecotourism. Conservation efforts have been aided by the proclamation of numerous protected areas, concentrated in the mountains and the West Coast area. The most significant threats are the encroachment of alien invasive plants and the rising risks of wildfires, as well as degraded river banks and wetlands. The Langebaan RAMSAR site serves to protect the rich biodiversity of the Lagoon and surrounding wetlands, including ca. 55,000 waterbirds in summer, many of them migrants.

Extensive land use change from natural fynbos and Renosterveld vegetation to agriculture and settlements has placed the rich biodiversity under threat. The area forms part of the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest of the six Floral Kingdoms in the world, but containing extraordinary high levels of terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity and endemism. This biodiversity ‘hotspot’ has immense intrinsic value for the healthy functioning of the ecosystems of the catchment, as well as having great economic value associated with wildflower harvesting and ecotourism. Conservation efforts have been aided by the proclamation of numerous protected areas, concentrated in the mountains and the West Coast area. The most significant threats are the encroachment of alien invasive plants and the rising risks of wildfires, as well as degraded river banks and wetlands. The Langebaan RAMSAR site serves to protect the rich biodiversity of the Lagoon and surrounding wetlands, including ca. 55,000 waterbirds in summer, many of them migrants.

Extensive land use change from natural fynbos and Renosterveld vegetation to agriculture and settlements has placed the rich biodiversity under threat. The area forms part of the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest of the six Floral Kingdoms in the world, but containing extraordinary high levels of terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity and endemism. This biodiversity ‘hotspot’ has immense intrinsic value for the healthy functioning of the ecosystems of the catchment, as well as having great economic value associated with wildflower harvesting and ecotourism. Conservation efforts have been aided by the proclamation of numerous protected areas, concentrated in the mountains and the West Coast area. The most significant threats are the encroachment of alien invasive plants and the rising risks of wildfires, as well as degraded river banks and wetlands. The Langebaan RAMSAR site serves to protect the rich biodiversity of the Lagoon and surrounding wetlands, including ca. 55,000 waterbirds in summer, many of them migrants

The Berg River catchment imports almost all its electricity requirements from the national grid through the utility ESKOM. This energy is heavily coal-based, with a small nuclear and gas component. Electricity supply has been strained for a number of years and this has impacted on all users countrywide. Until new generation capacity up-country comes online, economic development, especially heavy usage associated with some industries envisaged for the Saldanha Bay area and elsewhere, could limit accelerated economic growth. Additional electricity is required to fully service the growing informal settlements in the area. Within the Berg catchment, a few wind farms have been constructed but with small generating capacity. Further development of this renewable resource, together with solar power, is supported by national and provincial government goals but is currently held back by lack of investment and sub-optimal economic and regulatory conditions.

Mapping Application

This link will take you to a comprehensive beta-version spatial database (GIS maps) covering the categories Food, Energy, Water, Land and Biodiversity and a number of base, or background maps, for the Berg River Catchment in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. For Phase 1 of this project, the maps can be viewed at user defined spatial scales, and information on the attributes of a specific area can be called up by clicking on the area. Further information on what the layers mean and how to interpret them will be provided during Phase 2.

The prefix to each file name indicates to which category the database belongs. To call up a layer simply click on the open box to its left. To close the layer click on the box again to remove the tick.

To call up the Legend, scroll up to the top of the column and click on "Legend".

This site will eventually provide an interactive tool for local economic and development planning in the Berg River Catchment - watch this space.

Enter the Berg River mapping application by clicking here

Metadata

A file (Metadata file) summarising the set of spatial datalayers which can be accessed under "Mapping Application" can be downloaded here.

This file gives information on the Category, Title, Description, Source, Contact Person and Contact e-mail address for each datalayer. The descriptions are not comprehensive and the use is referred to the relevant contact person for further information.

Metadata is "data about data". It provides information about an item's content. For example, it describes when the data was created, by whom, the methods used, how the data was formatted, a short description of the contents, and possible restrictions in its use. In the context of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the reader is referred to the ESRI webpage on metadata.

Framework

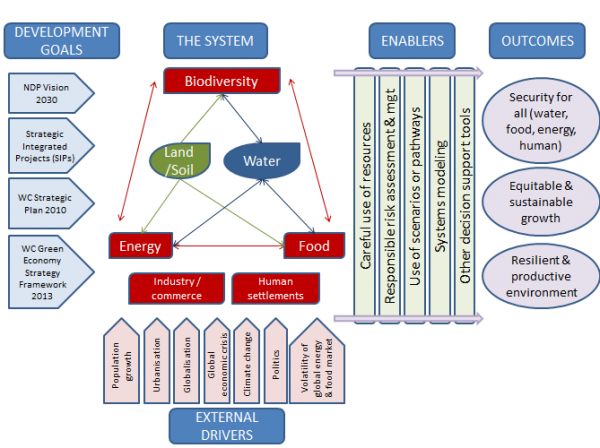

The FEWLB Nexus Project has developed a conceptual framework to provide guidance for nexus-based research, analysis and decision making in the South African context. The framework is applicable at multiple spatial scales, but will during this project be used towards a fine-scale analysis of the nexus in the Berg River catchment, as an example. It draws on other international nexus frameworks but brings in some new elements, notably a distinction between land and water as natural resources central to the functioning of food, energy and ecological production systems, and with competing allocations to human settlements and industry/commerce.

In the South African and Western Cape context, the national, provincial and municipal development goals provide the starting point for the nexus approach. They capture the social and economic complexities and needs at various scales. South Africa strives to ensure alignment between the various strategic plans through the IDP process, an integrated inter-governmental system of planning which requires the involvement of all three spheres of government. Provision is also made for contributions and comments from the private sector and civil society.

The Nexus Framework starting point and its envisaged outcomes are provided by, amongst others, the National Development Plan (Vision 2030), National Strategic Integrated Projects (SIPs), the Western Cape Provincial Strategic Objectives (2010), the Western Cape Green Economy Strategy Framework (2013), and the District Municipalities’ Strategic Objectives. The nexus-relevant cross-cutting objectives are inclusive economic growth, job creation and poverty reduction; improved infrastructure and service delivery; the transition to a low-carbon or green economy; and sustainable resource management and use. The outcomes (Hoff 2011) represent the three legs of sustainable development, namely society (the promotion of water, energy and food security for all), economy (equitable and sustainable growth) and environment (a resilient, productive environment). These outcomes could be achieved through specific governance and financial approaches, tools and decision support systems.

The Framework also accounts for external global, national and local trends and drivers which have a bearing on the pressure experienced within the nexus. These include population growth, urbanisation, globalization and the global economic crisis, climate change, politics, and the volatility of global energy and food markets. They can change the “state” of the nexus either quickly or in the longer term, and often in unanticipated ways.

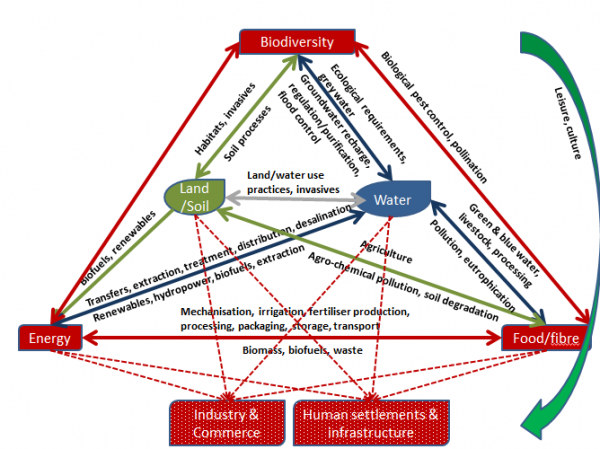

The central nexus (the ‘system’) depicts the extended FEW nexus agreed for this project – whilst the food-energy-water triangle is shown; a similar triangle exists for food-energy-land, for biodiversity-energy-land, for biodiversity-food-water, and so on. In other words, this framework places water and land/soil at the centre, representing natural resources which are extracted and used for biomass production (both cultivated and natural) and some forms of energy production. They are also used by humans for domestic and industrial purposes, and are intensively managed and allocated by humans according to agreed norms. If the nexus is to be used for policy development and project planning and implementation purposes in resource-constrained systems, resource management has to be the central consideration. Also, biodiversity should be given the same consideration as food and energy given its critical role in supporting sustainable production either directly or indirectly via the resource base.

The central nexus (“system”) can be further examined to describe the possible inter-linkages between the five elements. All linkages are dynamic and can operate in both directions.

The key interlinkages could be summarized as follows:

-

Energy-land-water:

-

Water is required for energy extraction and generation

-

Energy is required for the extraction, treatment and distribution of water

-

Land is needed for the production of biofuels and energy infrastructure including renewables

-

-

Food-land-water:

-

Land and water are primary resources for agriculture

-

Agriculture impacts on soil and water availability and quality

-

-

Energy-food:

-

Energy is required in the form of electricity and fuel for the production, processing, packaging, storage and distribution of agricultural produce

-

Biofuels, biomass and organic waste are used for energy generation and fuel production

-

-

Biodiversity-land-water:

-

Land provides habitats for biodiversity

-

Biodiversity and ecosystem services support soil development and fertility

-

Biodiversity and ecosystems need water to function (the ecological reserve)

-

Biodiversity and ecosystem services help to regulate hydrological processes and water quality

-

-

Biodiversity-food:

-

Insects and other pollinators provide pollination services to agriculture

-

Biological pest control reduces the need for chemical interventions

-

Sensitive farming can provide habitats for biodiversity

-

-

Biodiversity-energy:

-

Non-farm biomass provides wood fuel

-

Although not shown in this framework, fossil fuel-based energy and synthetic nitrogen-based fertilisers, as well as livestock farming, are linked to the production of greenhouse gases which leads to climate change and complex impacts on land, water, biodiversity and agriculture.

Human systems are also strongly linked to the nexus and are shown as external components. Water, land, energy and food are required for people in urban and rural settlements, and for industry and commerce. Biodiversity provides many positive opportunities for people in the form of leisure, sporting and cultural activities, and for well-being.

Project Report