El Nino Ready Nations’ project: A case study of South Africa

South Africa has experienced droughts since 2014, and is now affected by an extraordinary El Niño – a quasi-periodic event, returning at least once in any given ten-year period – that is having a number of effects for social and ecological systems. One of the major effects currently making media headlines is the significant decline in crop yields, and related concerns about regional food insecurity. According to FEWSNET (the Famine Early Warning System Network 2016), food insecurity will double in 2016-17. In South Africa, the national authorities recently recognised the urgent need to import 5 to 6 million metric tons of grains. This number rises to 10.9 million metric tons if one also considers regional food needs (FEWSNET 2016).

Uncertainties about El Niño’s teleconnected impacts on water, food and, ultimately on livelihood security partly explains the low level of preparedness in the southern African region. Yet, a lack of preparedness for food insecurity contrasts with the fact that the first appearance of El Niño conditions in the Tropical Pacific provided governments with the earliest possible warning of likely adverse impacts on water supply and food production. As the saying goes, “Forewarned is to be forearmed.” – but only if action is taken…

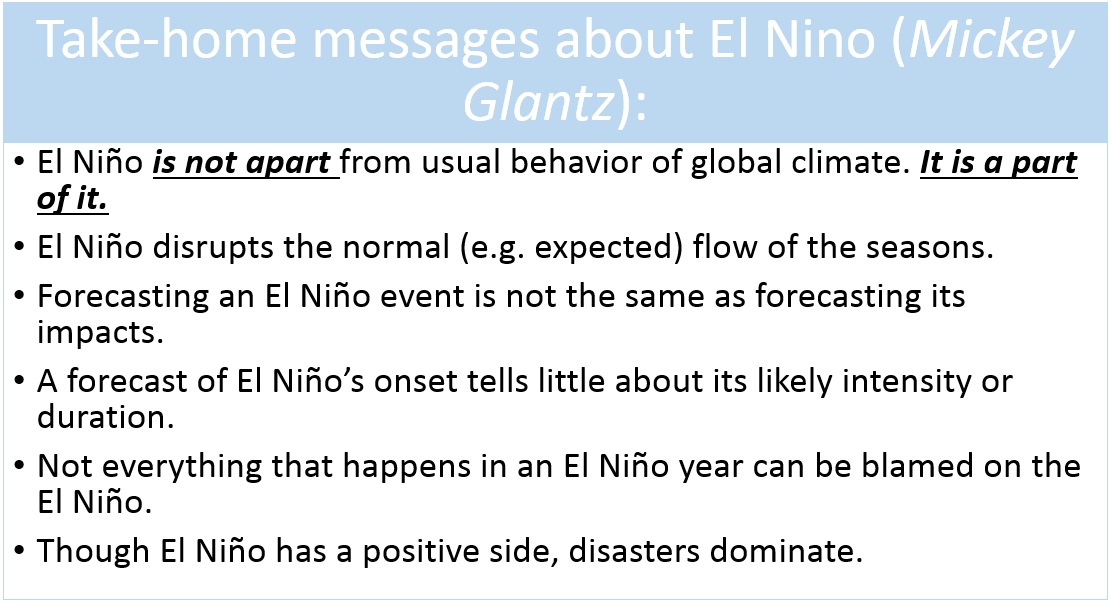

To better understand the (lack of) preparedness level for El Nino-related impacts, the ACDI is investigating the mechanisms and institutional arrangements for preparing for and responding to such events (and to droughts in general) in South Africa. This study is part of a Portal Project for Lessons Learned about Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) in a Changing Climate. The Portal project is run by the Consortium for Capacity Building (CCB), at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and funded by the USAID’s Office for Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). The project had an initial focus on lessons learned about hydrometric warning systems but, as it started at the time the onset of an El Nino event was forecasted, in the middle of 2015, an opportunity arose to focus on what scientists and forecasters define as an extraordinary El Nino in terms of magnitude. Plus, El Nino is an interesting phenomenon to look at as its detection provides time to build preparedness. With that said, however, forecasting an El Nino event is not the same as forecasting its intensity, duration or impacts.

The concepts of ‘El Nino Readiness’ and ‘El Nino Ready Nations’ are quite central to this international project which aims to identify lessons learned from the current and past El Nino-related events, impacts and responses in various countries, to collect and analyse them and to, finally, share them through an online portal. Sharing lessons from past El Nino impacts can contribute to improve risk preparedness, thus reducing the risk of disasters on society. But this can only occur if such lessons are compiled, shared and used, to influence decision-making processes.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to attend a ‘networkshop’ (a workshop which also facilitates a networking process among the participants) with 30 other researchers, climate scientists and practitioners in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR). The aim of the ‘networkshop’ was to discuss our progress in this project, our areas of focus and our priorities.

Image: Countries and cities represented in our study "El Nino Ready Nations".

The discussions were centred around pathways to build ‘El Nino Ready Nations’ (ENRN). Behind this concept is the idea that whenever a forecast is made – for instance, of El Nino onset – someone, , is (or should be) responding to this. Since the last decades, forecasting techniques have improved in terms of predicting ENSO extremes, thus one would think that responses have improved too. However this is not always the case, as the way information is used and integrated into decision-making processes still poses a challenge. Hence, the concept of ENRN inspires us to investigate the reasons why appropriate actions are not always implemented despite available information.

There are many aspects that could be investigated in order to fully capture why a specific country or region does or does

not prepare for El Nino’s impacts, and these include uncertainties in the climate science about the magnitude and the impacts of an El Nino in a given area, as well as issues in effectively communicating the information to relevant authorities. Of major interest is the ‘limited’ societal and institutional memory of past disasters, and the short attention span in governments and the public. In a context where many problems demand the attention of policy-makers, attention can shift quickly away from El Nino’s – especially after it has peaked. In other words, once a hazard has passed, it is no longer a priority… until the next event. So, when we talk about ‘El Nino Readiness’, the existing gap between society’s short attention span and El Ninos’ irregular occurrences must be kept in mind. Moreover, the issues of closing that gap and finding ways to sustain attention on El Nino, should also be investigated. The question is how do we ensure continuity of awareness and concern for El Nino, within society and amongst decision-makers?

One of the ideas expressed during our discussions in Bangkok is to promote a shift of focus from ‘El Nino’ as a single, irregular and sporadic event to the boarder ENSO cycle, which encompasses ‘normal’ and ‘extreme’ periods. After all, El Nino is part of a natural cycle and acts as an extreme that can disrupt the normal flow in seasons. Emphasising ENSO vs. El Nino could, perhaps, make society aware of the broader climate process, rather than focusing on the temporary extreme. We would then move from the concept of ‘El Nino Readiness’ to ‘ENSO Readiness’; yet, ENSO is not familiar to the public and its acronym is not memorable compared to the term ‘El Nino’, thus it would require lengthy explanations and awareness raising among the public and government.

With a spark of hope to address the ‘DRR implementation gap’ and sustain attention on the risks related to El Nino events, the Portal project aims to eventually set up an online portal where lessons about risk reduction will be collected, analysed and shared widely. Yet, at mid-course in the project now, many questions and concerns remain. For instance, establishing a ‘Lessons learned Portal’ does not mean that it will be used for decision-making –some of the key considerations regarding the utility of a Lessons Learned Portal need to be taken into account while designing it. This includes defining: who is the target audience of such a portal: climate scientists? Policy-makers? Practitioners?; How the information should be formatted or packaged to maximise the outreach?; What platform should be used in order to best share our lessons learned: for example, as contribution to existing DRR-related knowledge portals (e.g. Relief Web Portal)? Or a new portal? On social networks including Facebook and Twitter? All the partners involved in the El Nino Ready Nations project share these concerns; our strengths lie in the diversity of perspectives represented in our group – from climate scientists to academics – and our willingness to collaborate towards a same objective: improving disaster risk management in the context of a changing climate.

Of course, these 4 days in Bangkok were not only a workshop but rather a ‘networkshop’, meaning lots of opportunities to connect with old colleagues and friends, meet new ones, discuss potential collaborations, and together, enjoy some of what Bangkok has to offer!

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the author in his private capacity.