Why the talks in Paris cannot fail.

By Harald Winkler

To be judged a success, when the new climate treaty is agreed in Paris in December, we need an agreement that is able to solve the climate problem. That means keeping the global increase in temperature well below 2°C above preindustrial levels.

It has to be a fair deal that not only makes compromises among the rich and powerful but actively protects the vulnerable. It will almost certainly be a treaty providing agreed rules and some confidence that everyone will act.

The Paris Agreement needs to contain legal obligations and actions to implement commitments. Clear rules and timeframes must be set to guide implementation. Progress must be reviewed every five years to make targets stringent for everyone.

There is no longer any question that a treaty with the capacity to solve the problem is long overdue. The agreement comes after more than 20 years of climate negotiations, and 18 years after the Kyoto Protocol was agreed. That does not mean that it will resolve all the issues. The attempt to find one grand solution failed in Copenhagen.

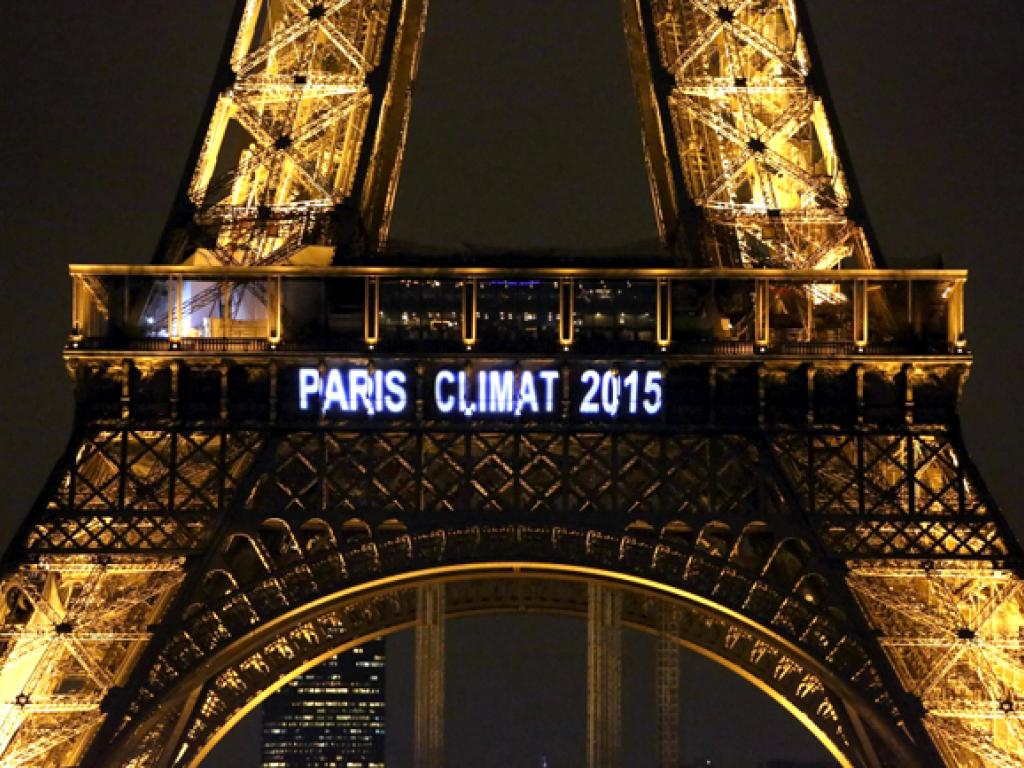

The agreement coming out of the climate change talks in Paris must be about countries taking responsibility for their vulnerable communities and citizens. Image Source: Business Day.

The lead-up to Paris has taken a different tack, seeking to broaden participation by calling on countries to offer their own "intended nationally determined contributions". This exemplifies a bottom-up approach. Yet the overall objective has to be at the heart of the agreement — keeping the increase of temperature well below 2°C above preindustrial levels. If it does not tackle that question, it will be a failure.

Setting in place an agreement with greater flexibility for individual nations, means the question "does it all add up to solving the problem?" is crucial.

"Is it a fair deal?" is the other central question that must be settled among the parties. Equity means that there has to be protection for the vulnerable; and that the finance, technology and capacity to implement are provided by richer countries.

The temperature goal should make concrete provision to support adaptation. This means setting a global goal for adaptation, as well as agreeing to work on methodologies for quantifying both effects and the investments required for national adaptation plans.

The Paris deal must enable support for instances of loss and damage. An example of "loss and damage" would be when a country loses half its gross domestic product and is no longer able to adapt in an incremental fashion. So expect Paris to be about adaptation (responding to the effects of climate change), as well as mitigation (reducing the carbon emissions that have led to climate change). There are good options for a long-term goal for mitigation.

The scientifically clearest choice is to divide up the remaining global carbon budget, which is shrinking at a rapid rate. Distributing that fairly is politically tough. So the mitigation goal may be framed as net zero emissions by the middle of the century. Whichever is chosen, the long-term goal must guide short-and medium-term targets.

THE bottom-up preparations for Paris have focused much attention on "nationally determined contributions" to mitigate and adapt. But why have a treaty if it contains no substantive obligations for parties? Expect the Paris Agreement to have both commitments and actions.

In relation to legal obligations, it is not sufficient to have good intentions when drawing up commitments. Countries also have to commit to implement.

The agreement should turn the intended nationally determined contributions into legal obligations. Countries will need to implement laws and policies that will achieve the outcomes they put forward — in addition to the commitments on adaptation, requiring countries to take responsibility for their vulnerable communities and citizens.

Some countries will need support to fulfil this responsibility, so the collective review every five years of what is being done is essential to keep track of implementation of adaptation. On mitigation, we already know there is an emissions gap — between what emissions reductions countries put forward internationally and what reduction is actually needed to keep the temperature increase well below 2°C. To implement the agreed measures requires action by multiple interested parties at every level of society — governments, companies, cities, nongovernmental organisations, independent initiatives and endeavours by individuals.

Paris should focus on enabling more action, by a wider range of actors. The agreement must send strong signals that greenhouse gas emissions will be phased out equitably. That will require shifting patterns of investment. Clearly the world has to learn to use less coal, and subsidies for fossil fuels generally should be phased out.

SA has long had an energy policy committed to diversity, but moving away from coal is taking time. Transitional options for electricity may include gas and nuclear, but in the long term, there is little doubt renewable energy is the most sustainable. It is a major growth industry globally.

We also need to change patterns of consumption, and our own behaviour. Pricing carbon and shifting subsidies to renewable energy, energy efficiency and affordable access to modern energy services — these are important actions we should expect to come out of Paris.

Some things cannot be expected from Paris, although perhaps they can be inspired by it. We need mind-set changes — notably that "living well" does not always mean increased consumption, that we can be happier with less. And use what we do more efficiently.,Despite the urgent warnings about climate change, the emissions gap appears to persist. We need to ask whether there is anything we can do together that is more than the sum of the parts.

The Paris Agreement is expected to capture autonomously defined contributions. Having a binding review process is crucial if this bottom-up approach is to be effective in the long term. It seems unlikely that the intended nationally determined contributions submitted by Paris will put the world on a path to a 2°C reduction. The gap between what is required by science and the politics of what countries are willing to commit to internationally is large.

As of October 1, 119 countries had put forward their intended contributions. Even with all of them implemented, emissions in 2030 will be much higher than what is needed to stay well below 2°C. This year’s United Nations Environment Programme emissions gap report is still being compiled, but the gap is likely to be in a range of 13-18 gigatons of CO² (the amount of CO² released into the atmosphere) for 2030. Paris must put in place a system, if collective efforts are not on track, and countries must increase their ambition. If the sum of efforts is not enough, reviewing and adjusting becomes important. A transparency framework for action and support is a critical basis.

Climate change is a global "commons" problem — it affects everyone, and can only be solved by collective action. Only when each country knows that the others will also act, can we all act together. So improving transparency and accountability through reporting and review is crucial.

The Paris agreement will need clear rules and time-frames for implementation. Fundamental to a multilateral rules-based system, such as a treaty, is regular reporting and review. The agreement should set up political discussion every five years to review what is being done on adaptation, mitigation and all that is needed to implement both.

Paris must deliver a treaty that is adequate to tackling the challenge of climate change. If it does not even set out to solve the problem, it will be judged a failure by history. And failure is not an option. You can’t negotiate with the climate.

*Republished from Business Day with permission from Harold Winkler is a Professor at the Energy Research Centre, University of Cape Town.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of the ACDI, or any other entity affiliated with the ACDI.