Should trees have standing – the modern alternative of the Rights of Mother Nature?

By Alicia Okeyo

What if a tree could hug you back?

It was not so long ago that I attended a very insightful talk by an eloquent speaker from the Edmund Rice Network – South Africa (ERNSA). Although the name of this speaker seems to now be lost in the cobwebs of my mind, I do recall the rather fascinating topic that she discussed, relating to Environmental Rights and Eco Justice.

“Earth Jurisprudence” – she began her talk with jargon that left most of the audience looking around at each other as if we had all mistakenly walked into a talk presented in Gaelic. Needless to say, I had to secretly Google the second word, to avoid looking like an ignorant audience member, who simply attended the event for the food (don’t get me wrong, who doesn’t love free food?) Simply put, the term jurisprudence refers to the philosophy of law. Having acquired this new information from my Google search, it led me to my next thought - Why would she (the speaker) couple the words ‘Earth’ with jurisprudence? The interesting discussion that followed succeeded in answering my question and more, which I will attempt to summarise as follows.

Emergence of Environmental Rights – the phase of human rights over nature?

According to the ERNSA speaker, the emergence of environmental rights recognition was preceded by what former Harvard Law professor Alan M. Dershowitz describes in his 2004 book Rights from Wrongs as the “human rights revolution”. Concurrently, there was the beginnings of a recognition, in the 1970s, of the growing environmental crisis that has since led to amended constitutions of both emerging and established democracies. Subsequently, the right to live in a healthy environment emerged, resulting in the need for constitutional provision to protect the environment. Significant environmental disasters such as the Torri Canyon oil spill of 1967 also helped cement the global agenda on environmental human rights, by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP). Despite this shift in perspective, there has still been a heavily anthropocentric approach to environmental rights protection that perhaps reiterates the long standing notion that man is dominant over nature.

Often human rights protect the environment for the benefit of mankind, and not for the simple fact that environment should be protected. For example, in an instance where a major coal mining company buys a piece of open land and wishes to destroy a pristine natural landscape in order to mine the land, the inhabitants of that land and its surrounds that benefit from the tourism the land generates, may exercise their rights to protect that land. The rights of these locals may include their property rights, as well as the right to demand access to information from the mining company before they go ahead with their mining plans. This process of invoking community and individual rights can be useful to delay or ultimately derail plans to mine this pristine landscape. In this way, man invokes his human rights to protect the environment that he may remain conqueror, and thus beneficiary of.

The trouble arises when these legal instruments fail due to the fact that, in reality, legalities are not black and white, and are often influenced by business and politics. Sticking to the example above, the ‘business-politics’ agenda may allow large corporations such as this particular mining company to be taxed for the potential environmental damage of their projects. Therefore, so long as they can afford this tax fee, they may proceed with business as usual. In this way the mining company may too exercise their rights to administrative action to propel their plans forward for mining this land. Consequently, in situations where legal systems act to perpetuate environmental destruction favouring ‘human (in this case the mining company’s) rights’, the notion that man is owner of the environment becomes problematic for the protection of the environment.

Should trees have standing – the modern alternative of the Rights of Mother Nature?

The example above depicts many reported and unreported cases that occur as commonplace throughout the world’s landscapes. Perhaps a second shift in human perspective, similar to the one described earlier that catalysed the environmental rights era, is now needed. Mankind needs to shift from a view that we are owners of the environment, to an alternative view of being co-authors in the Earth Community. South African environmental attorney and author Cormac Cullinan suggests that we need to move from the “false belief in human superiority to embrace our role and participation in the Earth’s community of life”.

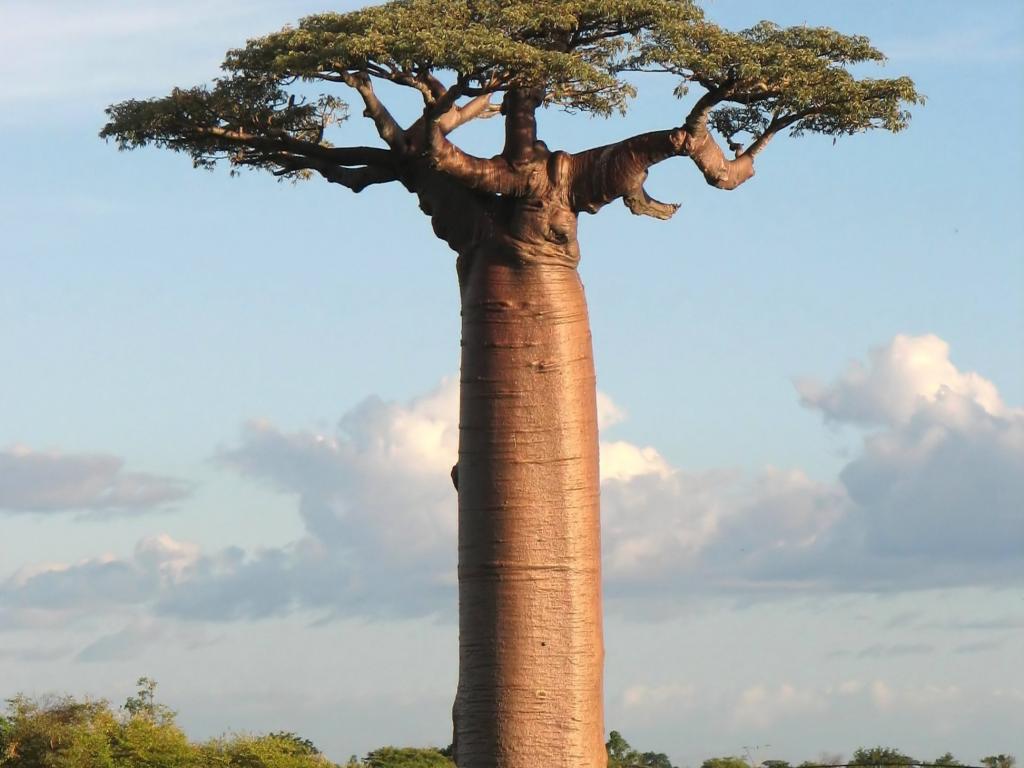

Similarly, Christopher D. Stone’s influential book Should Trees Have Standing? , has been updated and republished for the past 35 years, symbolising the book’s continued compelling argument that the environment should be granted legal rights (separate to that of humans). Stone’s enduring work serve as the definitive statement as to why trees, rivers, oceans, forests, animals, and the environment as a whole should be granted legal rights, so that the voiceless elements in nature are protected for future generations. Some institutions and governments have already begun to make the necessary shift towards this way of thinking; in Ecuador, a developing state that is outshining the developed economic powerhouses of the likes of the United States and China, is leading the efforts towards equal rights for Mother Nature. In Ecuador there is said to be a sense of respect for the environment amongst locals, embedded in culture and tradition; and the Constitution of Ecuador already gives rights to all biological features. Additionally, institutions such as The Rights of Nature Tribunal, which convened its second annual congregation to parallel the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP 20) last December, are also making significant efforts to protect the rights of natural environments. Significant wins have already been gained at this tribunal; one of the most famous being the case for the rights of the Great Barrier Reef, based on the Universal Declaration for the Rights of Mother Earth. According to the deceleration, trees (and reefs) should indeed have standing in court and in the fairness of life.

To date, no notion of environmental rights has yet achieved the desired sustainability impact that is needed for our generation. And while this is the case, hopeful enthusiasts such as myself believe that this new notion of the rights of Mother Earth and of human beings co-inhabiting (as opposed to conquering) the Earth’s living community, may be a powerful transformative step for the future protection of the environment.